How do you know if you have talent? What does it feel like?

In a 1989 study, sociologist Daniel Chambliss decided to find out. He chose to interview those in Olympics Sports, specifically swimming.

Why?

Because unlike in other areas, in competitive swimming, you always know the ranking, the speed, the time — all the statistics you need to tease out what makes performance good.

After interviewing around 120 world class swimmers and coaches, he found three things that differentiated those who excelled from the rest.

Lesson 1: It’s not how much you do but how you do it.

Ever wonder why many of us drive everyday but we can’t compete with F1 racers when it comes to driving?

Because high level performance is training in a qualitatively different manner.

Chambliss found that poor swimmers swim have poor techniques and they only improve when their training allows them to pick up that new technique.

He also noted parallels in other fields like academia: Writing a single article for a high-ranking journal is qualitatively different from writing many articles for minor journals.

It’s not the number of hours you put in. It’s the kind of skills you train for.

Lesson 2: Talent does not lead to success.

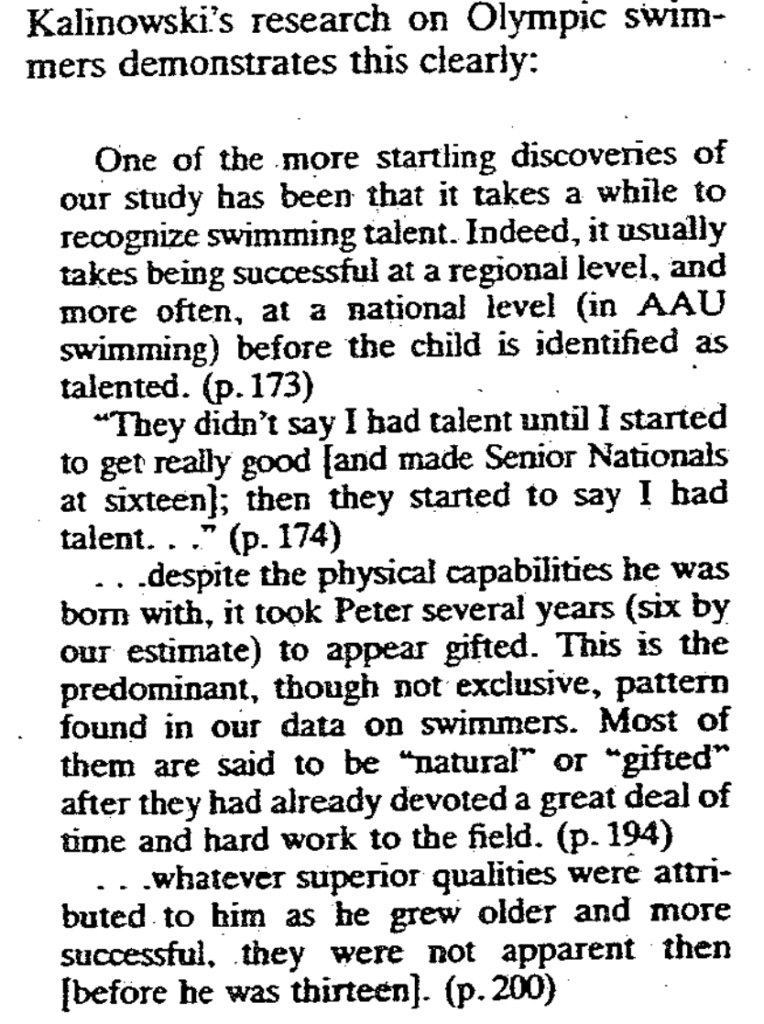

Chambliss also found that talent is not a useful term for determining who will do well in the future.

Many of us tend to attribute it to some kind of “talent” when we observe exceptional performance.

But swimmers are often labelled as “talented” only after they have started to perform well, not before.

Instead of an ambiguous “talent” label, it is more useful to talk about other factors like having access to pools during young, parental support, genetic endowments, etc.

Chambliss does not deny that innate advantages exist. But once a certain threshold is passed, they are less important than the will to keep consistently at it.

Lesson 3: Being good is a result of habits.

Chambliss also found that swimmers that perform well make exceptional performance part of their habit. By accumulating dozens of small improvements gradually overtime, they end up building a large edge over others eventually.

This means doing your best every time you train not only in competitions.

It also means to keep doing the same things over and over again, but somehow better each time.

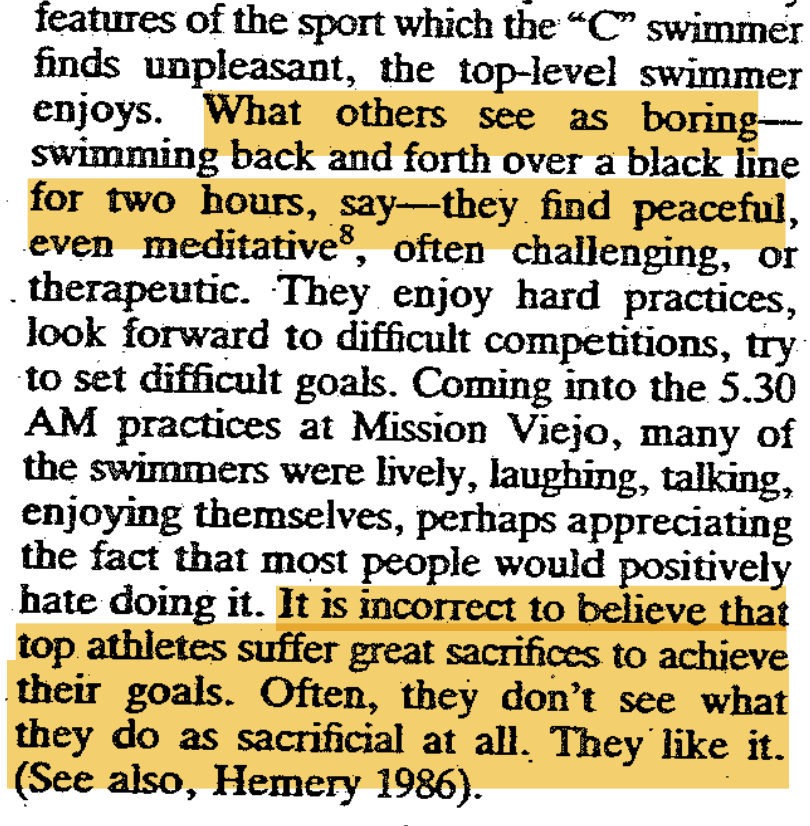

Sounds like torture? Not when you ask the swimmers. Many actually felt it was meditative or even rewarding.

Another crucial thing he found was what motivated these swimmers were not the big goals like getting the Olympic gold medal. It was the smaller wins like enjoying their daily practice with their team, being in the water, competing in the local competitions i.e. the things that help you show up everyday.

It’s only a torture if you don’t like what you are doing.

Bonus

Reading Chambliss’ paper, I can’t help but be reminded of Charles Darwin.

Unlike the other titans in science like Issac Newton or Albert Einstein, Charles Darwin was not noted for his intellectual prowess.

He is thought to be somewhere in the middle of a good private high school class. And because of his poor health, he doesn’t work more than a few hours per day too.

Yet, he managed to undercover one of the most important law in nature, by consistently and passionately pursuing his interest.

And that I think is the secret to being talented.