If mirrored reciprocity really works, why do good guys sometimes get the short end of the stick and bad guys come up ahead?

Should we keep giving favours even if the other side does not reciprocate? Isn’t winning everything the best strategy to achieve what we want in life?

Is it better to be selfish or cooperative?

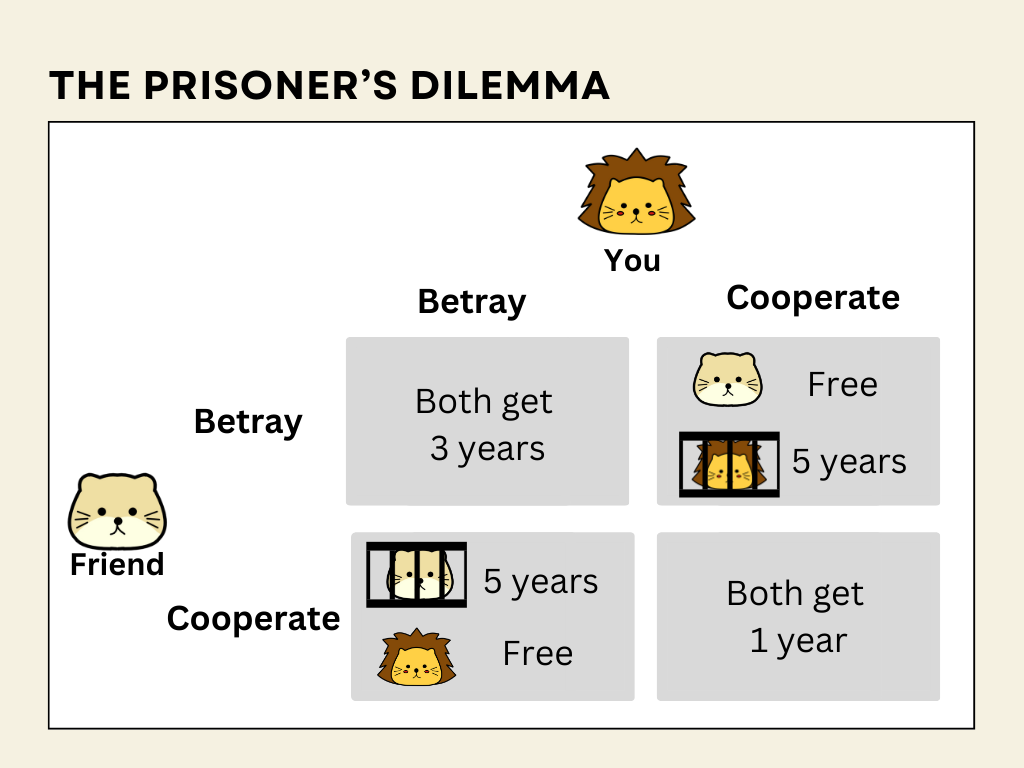

To study this, economists have come up with a simple way to represent this type of situation. Also known as repeated Prisoner’s Dilemma, two players have a choice to help each other, exploit the other person or suffer the consequences together.

To get a sense of how the Dilemma works, consider this.

Imagine that you and your friend have been caught for robbing a bank.

You are put in different rooms and being interrogated.

You don’t know what is happening in the other room and you have no way to communicate with your friend.

Now you have to make two decisions. Whether to admit to the crime yourself and whether you should testify against your friend.

If you both testify against each other, you both get three years.

If your friend testifies against you but you don’t, you get five years and he goes free.

If you testify that your friend was the mastermind and he doesn’t testify against you, you go free and he gets five years in prison.

If you both refuse to testify, you both get one year.

What would you choose to do?

When it is a once-off game, many people would actually choose to testify. After all, there’s a chance you get away scot-free and also avoid the fear of being the sucker (What if he testify while you stay silent?).

However, in real life, our relationship with others are often long-term. So what happens if the game is repeated over the long run?

Good guys beat bad guys in the long run

During the 1970s, Robert Axelrod ran a tournament where different computer programs with different strategies play Prisoner’s Dilemma together to see which one racked up the most points. The strategies come from the various disciplines from mathematics to psychology.

Here are some of the strategies:

– Tit-for-Tat(TFT): cooperate on the first round, then in every subsequent round, retaliate/reciprocate accordingly based on what the opponent did previously

– Random: cooperate or defect at random

– Nice Guy: always trust and cooperate even after being screwed over

– ALL D: always betray

– Tester: track the other player’s moves to see how much it could get away, cooperate if caught betraying its opponent

In the beginning, those who played nice lost points and the bad guys quickly rose to become the top scorers. Yet, gradually, Tit-for-Tat(TFT) started to make a comeback. When TFT met a program that cooperated on every move, the gains were enormous. And as it learnt to punish those who defect, it reduced its losses. Finally, after all the rounds, TFT won.

Why was TFT so effective?

TFT did not only give by cooperating. It was also able to punish and teach. It showed the other players how to play better. Programs like Tester learned that playing along was more beneficial than the marginal gains earned from defecting.

The bad guys also had a few things going against them. As the rounds proceeded, the bad guys started to “get a reputation”. Once the other programs learnt that they would always defect, these programs stopped cooperating with them. This created greater losses overtime for the bad guys.

It seems like good guys do win after all.

All this sound so simple.

Yet, there are at least three things that are stopping us from achieving it.

Envy

In the tournament, TFT never got a higher score than its counterpart did in any single round.

It never won. But overtime, the gains it made on the whole, beat those who always “win”.

Will you be able to cooperate if the other side got more than you?

Forgiving

After the first tournament, Axelrod conducted a few more tournaments to find ways to beat TFT.

The final, best strategy was a generous TFT. Instead of immediately retaliating when the other side betrayed, it sometimes choose to cooperate again. This allowed TFT to also cooperate with other programs that was not totally evil or utterly random and brought out the benefits of cooperation.

On the other hand, the not-nice programs were not able to get more points because they could not forgive and cooperate. As a result, they got caught in death spirals of retaliation, replicating the saying: an eye for an eye, makes the world go blind.

But we all know how hard forgiving can be. This means overcoming the sunk cost of any sacrifices that we have made, the pain of betrayal, etc.

In real life, your counterpart may be someone you dislike. Are you willing to see them win alongside with you?

Are you willing to forgive those who made mistakes in the past?

If You Could See the World the Way I See It

Last but not least, unlike in the program where all the programs have the same objective, we humans have different needs.

To cooperate well then often entails understanding what it is the other party wants.

Roger Fisher, in his classic negotiation book Getting to Yes, tells the famous “orange story”:

Imagine there are two sisters fighting over one orange. Both want the whole orange and the argument escalates before mum steps in. In an effort to stop the fighting and to be fair to both children she grabs the orange and cuts it straight down the middle to give each child an equal half.

But the whinging she was trying to put a stop to continues and escalates! Why?

Little Emily explains that she needed the whole orange to squeeze out enough juice to complete her orange cake for the school baking competition, and little Lucy wails that she needed the whole orange because her class was having a competition to see who could peel the longest orange rind off in one continuous spiral!

If only the girls had spoken to each other to explain what they wanted. If only mum had stopped to ask both girls what it is they needed out of the orange. Then both of their needs could have been met. Lucy could have painstakingly peeled off the orange rind and Emily could have then had the fruit to juice for her cake.

While it is a simplistic story, it does illustrate how we tend to assume the other party wants the same thing as us. But if we are able to share and communicate effectively, we will quickly discover the best way to achieve win-win for both parties.

Unfortunately, poor communicators tend to think that as long as they say what they think is true, they have communicated it well. The problem is of course that true communication is a two-way street.

The classic book “On How To Read A Book” compares the role of the writer/communicator and the reader/listener to that of a batter and a pitcher in baseball. The writer communicator starts the game by throwing the ball, which is the message. The batter receiver has to learn to catch the ball.

Sometimes, the ball is poorly thrown. Sometimes the batter is bad at catching the ball. But regardless, both must work together in order to get the ball across to the other person.

To communicate well means you have to try to see the world the way they see it — their needs, their aspirations, their insecurities, their time horizons.

This may not be easy. But it is critical if you want to win in the long-run with important partners in life.